The recording starts with the patter of a summer squall. Later, a swaying tone that sounds like a radio station that isn't quite tuned in rises and briefly drowns out the chatter.

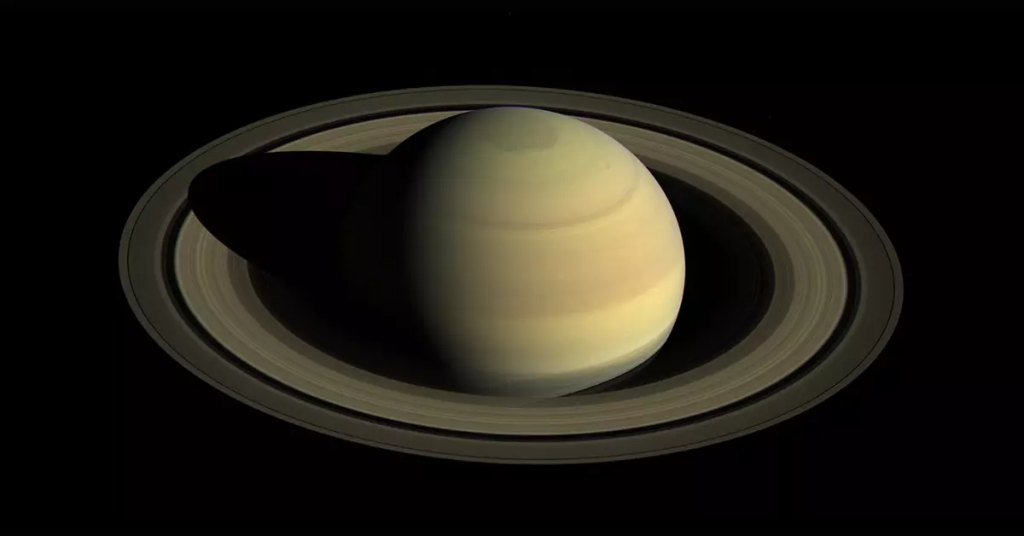

These are the sounds that NASA's Cassini spacecraft heard on April 26 as it swooped through Saturn's opening between its innermost ring and the planet. These were the first 22 encounters the spacecraft will have before entering Saturn's atmosphere in September.

Numerous dust particle collisions that the spacecraft experienced as it traveled through the rings' plane went undetected by Cassini.

The principal investigator for Cassini's radio and plasma science instrument, William S. Kurth of the University of Iowa, said, "You can hear a couple of clicks."

According to him, the few recorded dust hits sounded like the tiny pops brought on by dust on an LP record. Dr. Kurth claimed that the noise he had anticipated was more akin to "driving through Iowa in a hailstorm."

Scientists and engineers had no idea what to expect because Cassini had never traveled through this area before. At a speed of more than 70,000 miles per hour, Cassini would pass within 2,000 miles of the cloud tops, putting it in danger if a sand grain were to hit it accidentally.

Although the likelihood of such a collision was low, mission managers decided to wait until the mission's final months to send Cassini here because they considered it risky. The spacecraft was pointed with its large radio dish facing forward, acting as a shield as a better-safe-than-sorry safety measure.

There wasn't anything disastrous there wasn't much at all. A micron, or one-25,000th of an inch, in diameter dust particles the size of cigarette smoke, produced a few clicking sounds.

For the record, Cassini did not hear any sounds. After all, it travels through space, where there is no air and no vibration of air molecules to transmit sound. However, the radio waves that Dr. Kurth's device captured from outer space can be converted into sounds just like the ones that the Earth's atmosphere uses to broadcast artists like Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Bruno Mars.

According to Dr. Kurth, the background noise was probably oscillations of charged particles in the upper ionosphere of Saturn, where solar and cosmic radiation breaks down atoms. When the charged particles oscillate in unison, the louder tones are almost certainly "whistler mode emissions."

The sound produced by the dust particles is unique in its own right.

When the dust and a small portion of the spacecraft make contact with Cassini, they vaporize into tiny clouds of extremely hot gas that produce radio waves when electrons are ripped from atoms.

The actual physics is still a bit controversial. According to Sigrid Close, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford, "people aren't sure what they're seeing."

Her theory, which is supported by lab tests and computer simulations, states that the lighter electrons initially move away from the ions more quickly, creating an electric field that pulls them in that direction, where they then oscillate back and forth.

Lightning produces pulses of a similar radio frequency, she claimed.

This may be a crucial process for spacecraft closer to Earth, such as military and commercial satellites in orbit around the planet since pulses produced by intense dust strikes could damage their electronic systems.

The number of dust impacts per second when Cassini passed through a weak Saturn ring in December was in the hundreds.

Cassini can conduct additional scientific observations because it does not need to use its antenna as a shield. After all, the gap between Saturn and its innermost ring is safe.

Tuesday saw the first direct examination of the ring particles by another instrument, the cosmic dust analyzer, during its second dive through the gap. The dust analyzer can now record particles smaller than radio waves could have picked up during the initial pass. Additionally, Cassini made magnetic measurements that will be used to calculate the size of a Saturnian day. Saturn's clouds make it difficult to determine how quickly the underlying planet rotates, so this remains a mystery.

On Wednesday morning, Cassini reconnected with Earth and is transmitting the findings of the second dive.