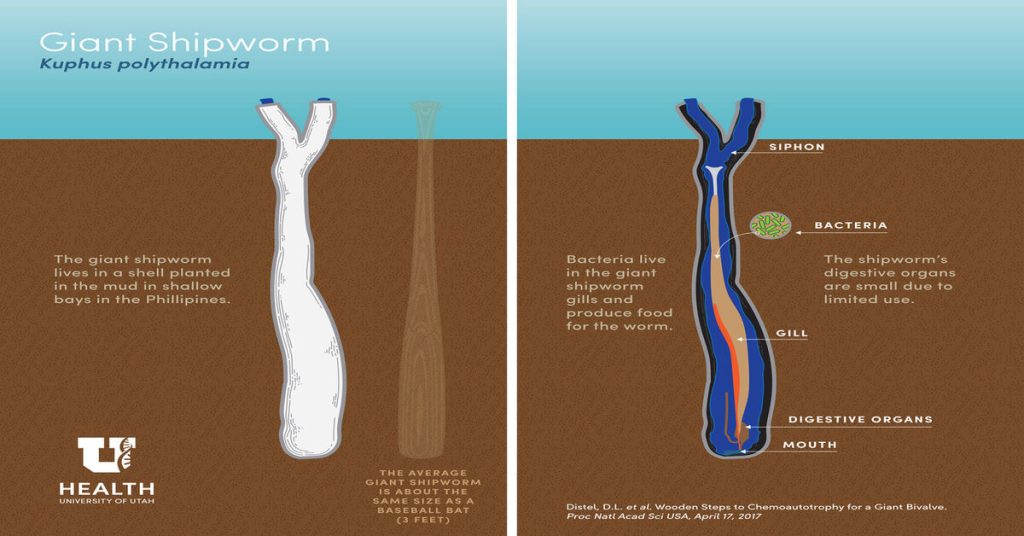

What you see is a giant shipworm, a scientific myth that can reach lengths of more than five feet. In reality, it's a mollusk that grows vertically in sediment, producing a thick shell and two siphons that protrude from the muck. Biologists agree that it is bizarre. Depending on your line of work, that may not be safe for the workplace.

These biologists have known how these tusk-like shells were created for a long time, but they could not obtain a live animal. It wasn't until 2010 when a scientist watching Philippine TV by chance saw a documentary about the men who dive for the objects that they were finally located. It will remain a secret as to exactly where in the Philippines. To protect the species, marine biologist Daniel Distel and the other researchers who write about the creature in today's Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences are withholding the location because the shells can sell for $200.

The shipworm may be a term you are familiar with. If we're completely honest, it's a pest because it destroys piers and bores through wooden boats. It only grows to a maximum length of two feet but is much skinnier than its girthy cousin. Why on Earth would the enormous shipworm enlarge itself so much then? That has been a mystery for decades, but now that scientists have their specimens, they can finally solve it.

Distel had a theory about the enormous shipworm, known as Kuphus polythalamia, before he had a living specimen. The typical shipworm can chew through wood but cannot digest it. Therefore, the fish's gills are home to unique bacteria that produce enzymes that travel to the gut and break down the cellulose in the wood into sugars for simple digestion.

Figuring out the mystery of the giant shipworm, a five-foot-long scientific myth

When we discovered that the tube's bottom was sealed, Distel says, "that seemed reasonable, but it seemed to sort of contradicting that idea." Distel speculated that the enormous shipworm might be somehow using the copious amounts of decaying wood in the Philippines' shallow waters. It might have lived like an earthworm, sifting through the mud to remove organic matter. If the end of the giant shipworm's tube was sealed off, what would it do with all the waste it produces? After all, earthworms ingest tons of dirt and spew it out the other end.

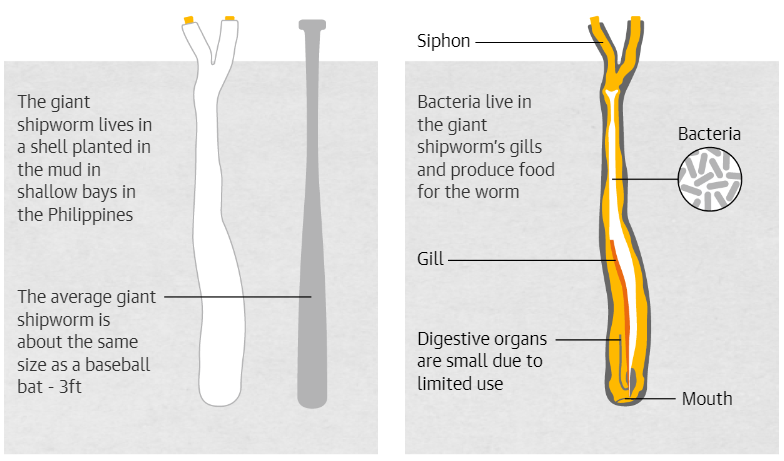

Then how about filter feeding? Perhaps the enormous shipworm is drawing plankton from the water using those exposed siphons. Although almost the entire body is filled with this large gill and all of their digestive organs are greatly diminished, microbiologist Margo Haygood, a co-author of the study, says, "we don't think that's a major part of their nutrition."

A big clue is that large gill. It may use specialized bacteria to break down hydrogen sulfide rather than wood, like deep-sea tube worms congregating around hydrothermal vents. Such vents release this foul substance, also widely present in the Philippines' decaying mud.

Unlike a typical shipworm, Distel discovered bacteria when he opened up the first living specimen and peered inside that massive gill. However, after sequencing the bacteria's genome, he and his colleagues discovered genes other bacterial species use to break down hydrogen sulfide. Accordingly, it seems that the shipworm consumes hydrogen sulfide, which the symbiotic bacteria then turn into energy for the host.

Because the bacteria do the work, a large gut is not required, which explains why the giant shipworm's gill is so large and its digestive system is so tiny. Haygood states, "it's kind of like an evolutionary convergence." It resembles the enormous tube worm at the hydrothermal vents in some ways. This organ, which is symbiont-filled, takes up the majority of the body cavity. The giant shipworm grows so large because its environment, like the deep-sea vents, is constantly replete with the toxic hydrogen sulfide, which other animals would never mistake for food.

But how did the enormous shipworm differ from its wood-eating relatives so drastically? The giant mussels that live in deep-sea vents may hold the key. Distel discovered in 2000 that a tiny variety of mussel, no larger than a sesame seed, feeds on the hydrogen sulfide produced by rotting wood and breaks down the gas with the aid of symbiont bacteria. A mussel like this might have descended to the hydrothermal vents in the distant past in search of the abundance of hydrogen sulfide, growing enormously in the process.

Perhaps the giant shipworm evolved similarly. According to Distel, if an ancient shipworm acquired sulfur-oxidizing symbionts, they would have lived in an environment with both hydrogen sulfide and their usual diet of wood. As a result, it served as an evolutionary stepping stone that enabled them to switch from eating wood to surviving on hydrogen sulfide.

So an enormous mollusk mystery suddenly becomes understandable. And, I suppose, a little bit stinkier.